THE OVERLOOK FIELD SCHOOL: MAINTENANCE

With Associate Prof. Liska Chan and Teaching Assistant Ali Pougiales; The University of Oregon Overlook Field School; Fuller’s Overlook, Dalton, PA; Mixed Undergraduate and Graduate, Summer 2018

“We have so thoroughly domesticated the earth and modified natural processes that it is no longer possible to speak of nature as something with a separate existence… the world is now entirely of our own making.” (Peter Coates, Nature: Western Attitudes Since Ancient Times, 176).

Viewed broadly, maintenance reflects humanity’s relationship to the natural world—it is a physical manifestation of that relationship. The terms of that relationship are culturally contingent, driven by a region’s demographic needs, available natural resources, and technological capacities, among other things. At various historical moments, civilizations have asked the same question—are we part of nature or are we above it?—and arrived at radically different conclusions. Since the European Renaissance, an ideology of separatism has prevailed. In the post-war era, in light of mounting environmental trauma, a view of nature as something with autonomy and value independent of its relationship to humans has gained popularity in discourses from philosophy to landscape architecture.

Today, the spatial and temporal scales of maintenance are such that its impact is difficult to measure—occurring not only across seasons, but over decades and centuries. It is such that we often don’t know what to attribute to maintenance or to natural forces. As philosopher Timothy Morton might say, maintenance is massively distributed. Thus, it can be difficult to perceive where—and when—maintenance starts and ends.

In most modern landscape architectural contexts, maintenance is a tool of distinction. Maintenance regimes yield categories of landscape. The same landscape, maintained differently, acquires a different name and, often, a different purpose. Not surprisingly, then, conventional maintenance regimes operate in the service of clarity, simplicity, replicability, and erasure. They are rarely spontaneous, complex, adaptive, or generative of designs.

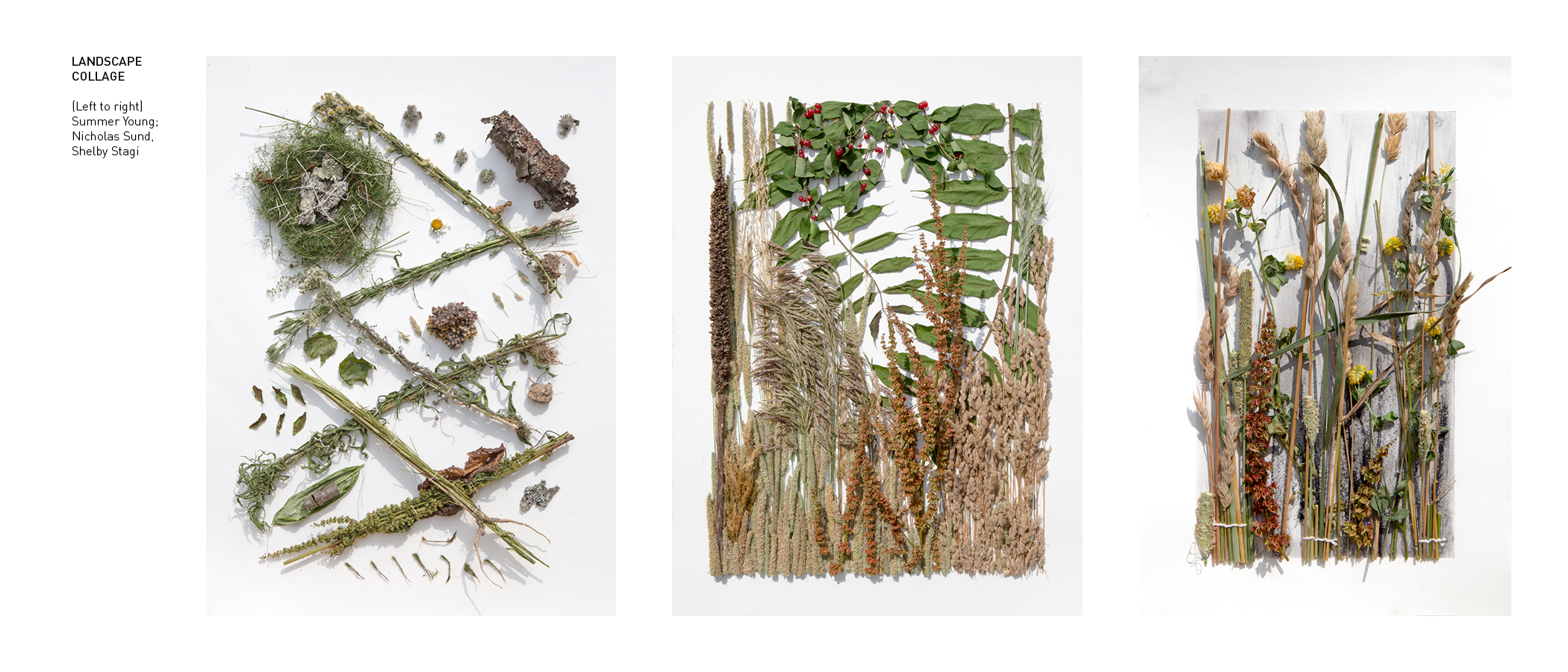

In this summer course, students were asked to consider existing systems of maintenance at Overlook and its immediate context and to develop new ways of relating to and maintaining this landscape.